Dear Friends!

Hereby we are starting a new series under the title LOOKOUT where time to time we will introduce a foreign paratrooper whom we have met during our work as a living history group. We have covered a similar topic in the past when a former British recon soldier shared with us his story. Goal of this new series is to give an insight to the everyday life of airborne soldiers of the era we are representing from around the world. In the interview below we will introduce to our readers Mr. Antonov Alexander, who has served in the airborne forces of the former Soviet Union. We would like to highlight the help of Mr. Vsevolod Chirkov for his help with the interview. We wish everyone a good reading!

Recon Blog: Please tell us about yourself.

Alexander Antonov: I was born in Leninogorsk of the East-Kazakhstan region (Ridder, Kazakhstan today), on June 20, 1970. When I was two years old, my family moved to Syktyvkar in the Komi Republic, within the Soviet Union of course. I think it’s important to mention the Finno-Ugric based Komi-Hungarian relations, as we are thus relatives. I still consider myself Russian, though. We lived just like everybody else in the Soviet Union.

When I was 7, I decided to pledge myself to the “heavens”: I wanted to become a pilot. Spoiler alert: I never made it. I’ve been dedicated to shooting sports since 1982; I love them. The first time I picked up an AKMS assault rifle was in 1984 during my first military basics class in school. We were told that airborne soldiers were using such weapons.

During a class recess in 1985, I noticed a flyer advertising a parachutist training. It sounded exciting, so started to attend classes and practices 3-4 times a week after school time. During the theoretical instructions we got acquainted with the D-5 and Z-5 parachutes (main and reserve parachutes – R.B.). When we asked our instructor how many jumps he had, he said “A couple… around 100”. We were completely shocked, thinking it would take a lifetime of parachuting to get a hundred jumps.

The training lasted about 3-4 months, with several tests. Once we passed those, we commenced with our first practical class, meaning our first jump. We first had had to excel at the so-called Military Pentathlon that included shooting, cross country running, swimming, throwing, and an obstacle course. The parachute jumps came afterward. Later on, the flying clubs of the Soviet Union were preparing the youth for their military service, with Ministry of Defense funding of course.

After my 3rd jump I realized that this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, so at 15 years old I once again pledged myself to the “heavens”, this time for real, and started parachuting.

R.B.: What was your motivation for becoming an airborne soldier?

A.A.: It was no question which branch of the military I’d serve in. My older friends and acquaintances were all airborne; several of them with deployments to Afghanistan. They were excellent role models for 15-16-year-old Soviet kids. I had also seen the 1979 cult movie called “In the Zone of Special Attention” which also influenced my decision. Courtesy of the parachuting and training camps, by the time I was drafted in the military I had about 400 jumps. The draft board was also unanimous, saying “Where else would we send him? Airborne!”.

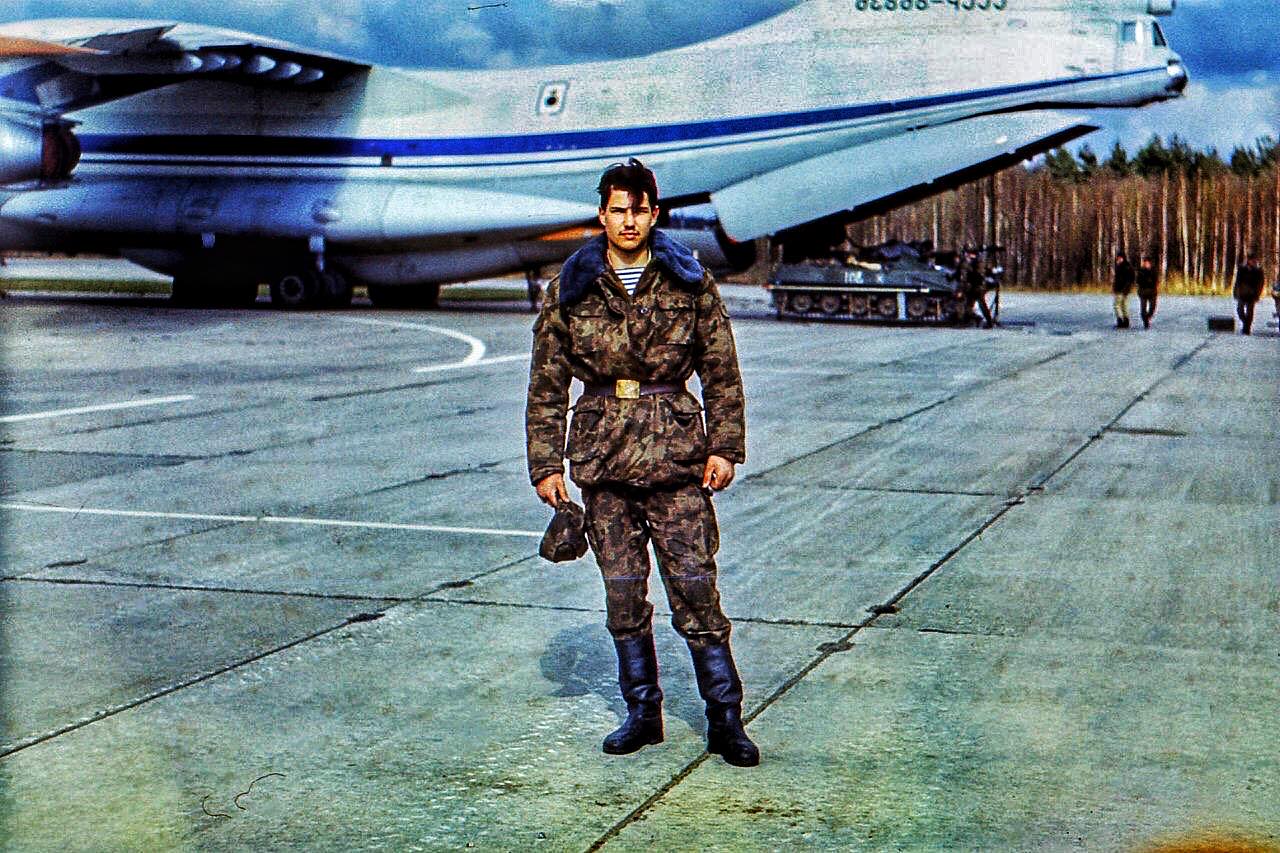

The young paratrooper

The young paratrooper

R.B.: When were you drafted?

A.A.: I was 18 when I received my draft order, or the letter commanding me “to repay my debts to the Motherland” as they used to put it at the time. All my future plans had to be deferred by 2 years to my 20th birthday. Before the completion of the military service, no Soviet boys could even start planning anything for their future.

I was drafted to the 242nd Airborne Training Center (242-й учебный центр подготовки младших специалистов Воздушно-десантных войск – R. B.), at Gaižiūnai, in the Jonava district of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania. After the completion of the training I was transferred to the airborne school of Kaunas, where I had to master a 6-month specialization course.

The huge differences between the soldiers of the various companies were already palpable in the training battalion. I was quite lucky to serve in a company that was quite “messy”; it’s difficult to explain, but back then many things were not taken seriously, despite the secrecy and the special circumstances.

After basic training I requested of my CO to stay in the town of Kaunas. After so many years I can still say I love this town and its people. It’s like standing in a window, taking a breath of fresh air. It was a window to a different world, back in 1988.

Following the training I was sent to the 7th Guards Mountain Air Assault Division of the Red Banner Order and the Kutuzov Banner Order (“7-я гвардейская десантно-штурмовая Краснознамённая орденов Суворова и Кутузова дивизия” – The predecessor units of this division fought in the Battle of Budapest in 1944-1945 and around Lake Balaton; and have participated in the taking of the Tököl Airport in 1956, as well as the crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968 – R.B.). Although the division’s airborne commander thought it was a bad idea, they eventually allowed me to stay in Kaunas.

During the Soviet times, the military was he place with the best opportunities in sport, especially parachuting, with the best instructors, bases, and huge funding. So, I managed to remain in the town of Kanunas. It didn’t take special efforts to make it into the division’s sports team. Our life was markedly different in the sports team compared to the training and service units. We had a 5-man team including me, of mostly non-commissioned officers and reenlisted soldiers.

One month after my transfer my service in the sports team has come to an end. My name has been crossed out due to a “daily routine violation”. Unofficially: I had a conflict with an older team member. I vehemently reacted to injustices.

During a break in training

During a break in training

R.B.: What nationalities served in your unit? How many Hungarians?

A.A.: Slavs gave 95 percent of our unit. During the selections I mostly met with Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians; many from Siberia. No Hungarians served in our unit. We never thought there even existed paratroopers of other nationalities.

R.B.: Could you describe your equipment?

A.A.: We mostly wore sweat suits. We had parachute jumps all the time, we cooked for ourselves; we practically lived at the airport. During training we wore the old style (1969M – R.B.) fatigues, made of cotton, with copper buttons and old-style cut. During winters we wore woolen fatigues. We still wore the “pilotka” hat, but our collar tabs and epaulets were airborne blue. During the training, however, we had not been allowed to wear the blue berets of the airborne, and we could unfasten our top button to show the “telnyaska” (the sky-blue and white striped T-shirt – R.B.) like a real airborne. After we were transferred to the 7th Division, for a short time we wore the old fatigues, but later received the “Butan” camouflage (1988M “TTsKO” 3-color – R.B.) fatigues, the blue berets, and all the accessories of airborne soldiers. During the weekdays, though, we wore the camouflage “kepka” (vizored cap – R.B.)

Illustration of the uniforms worn by Mr. Antonov during his service

Illustration of the uniforms worn by Mr. Antonov during his service

R.B.: Did you experience any interservice rivalry?

A.A.: There was a pontoon bridge engineering unit nearby. They wore black epaulets and collar tabs. We would tease them all the time and treat them with contempt. They had this saying, “If you are airborne, be proud of it. If you’re not airborne, be happy about it.”

We only showed respect toward pilots, due to their blue epaulets, and marines. We even had combined wargames with the marines at the Kaliningrad region. The objective of these exercises was to create bridge heads. We were dropped in, and then the marines came in from the sea.

R.B.: Were there any special initiation rituals for the new airborne troops?

A.A.: Not really. After the first jump we received our parachutist badges, and the nickname “Tashotnik” (“тошнотик” = sick in the stomach, referring to newbie paratroopers throwing up due to the excitements of the first jump – R.B.).

R.B.: How many jumps have you got?

A.A.: My first military jumps were from IL-76 aircraft at my training unit. Military jumps were not really challenging for me. As I said, by the time I was conscripted I had had over 400 jumps. I had another 115 or so jumps in the sports team, so altogether I was discharged with over 500 jumps. It’s important to note, however, that aside from the sports jumps I only have about 20 proper military jumps. We spent a lot of time checking our equipment and parachutes. Everything was always done with precision, but still 5 soldiers were killed during the practice jumps.

R.B.: Tell us about the jumps. Which one was the most interesting?

A.A.: I vividly remember the “Zapad-89” wargame (“Запад” = West – R.B.), where I performed 4 practice jumps and 1 combat jump. (Since the Soviets considered the Warsaw Pact countries as occupied nations where the military was on constant alert, all parachute jumps performed there during international military exercises counted as “combat jumps”. – R.B.) I jumped with a GK-30 type cargo container with additional weapons, ammo, and other equipment. Once the main parachute opens, the cargo container is disconnected with a special ring, and hangs 16 meters below us on a rope. The package is attached to us with a spring-operated system. The container touches down 3 seconds before the trooper, thus slowing the vertical descent and mitigating the possibility of injuries. I found this rig especially interesting.

GK-30 container in action

GK-30 container in action

After this exercise 15 of us received the “Expert Parachutist” title and badge, and we could shed our insulting nicknames. Lots of troopers sported this badge when they became reservists, but few of them truly deserved it.

Before a training jump

Before a training jump

R.B. How and where would your unit have been deployed during an actual war?

A.A.: In case of a real conflict, our division was to create a bridge head in the Federal Republic of Germany. Officers told me this, off the books. We could of course never see the actual deployment plans of our unit. But the “Zapad-89” wargame was pretty much a live exercise for us.

Since all sorts of internal conflicts were common in the Soviet Union, the airborne units were the ones deployed at any and all regions, due to our quick reaction capabilities. We soldiers had of course no clue that the Soviet Union would cease to exist in 1991. As political information, we were always told that the Lithuanians were the bad guys and the ones to blame. But they said the same thing to the other units about all the other nations wherever there was a conflict.

After 1989, on several occasions we woke up to real alerts. We immediately had to go to the airport, don the parachutes, and the aircraft were on the ready. The older NCOs, who had more wargames under their belt, including the “Danube-85” exercise, told us that if the warehouses at the airport were opened (where the mobilization stocks were stored – R.B.) that meant we were going to war. 10-12 hours after the alert we returned to our regular stations. One time, I cannot remember which country was the target, but it was definitely in Africa. We didn’t even know we had a mobilization agreement with them. I was onboard the aircraft by accident, as one of the parachute instructors. I was only there to teach the soldiers how to use the parachute.

R.B.: Could you tell us about the famous “dembel” (“demobilization”, the making of unique and spectacular discharge uniforms at the end of one’s service) and the infamous “Dedovshchina” (“reign of grandfathers”, the bullying and hazing of the junior conscripts by the seniors)?

A.A.: The preparations for one’s discharge from service is a huge and separate topic. We mostly remodeled our walk out uniforms. It was a difficult job, for you had to find all the proper materials. There was a “tank factory” nearby; well, at least that’s how we called it. They repaired armored vehicles. We acquired tons of stuff from them, especially nickel plated and chromed things. The whole uniform was reborn, except for the badges.

Hazing was not really a thing at our unit. The only issue was with those soldiers who served less than 1 year, as they were also responsible for the order of our unit. But we didn’t have any real reign of grandfathers.

Ready for demobilization

Ready for demobilization

R.B.: Do you have a message for the Hungarian veterans, collectors, and reenactors?

A.A.: I want them to know that for me it was a thrill to serve, same as for my Hungarian brothers. Of course there were hiccups, like everywhere else in life, but I was able to pursue my favorite sport during my conscripted service. For collectors and reenactors here’s my special offer: I’m happy to help anyone interested in this topic.

R.B.: Thank you for the opportunity and the interview.

A.A.: Thank you for having me and showing interest. Slava VDV! (Airborne greeting: Слава ВДВ, “Long live the Airborne – R.B.)

– Attila Pap –

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.